I want to start with a paradox that touches one of the central nerves of modern culture. “Speak your problem,” “set your boundaries,” “give space to your feelings” — these formulas, born in the depths of psychoanalytic practice, have seeped into popular consciousness. We are used to seeing any misunderstanding as a technical glitch, fixable through a properly structured dialogue. Perhaps that’s why Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata today seems like a careful dismantling of this naive belief. The film doesn’t explore a mere communication failure, but something far more complex: the tragedy of almost-understanding, when the characters briefly come close to hearing each other — and then pull back, realizing that the flash of clarity doesn’t free them, but instead exposes the fundamental impossibility of true encounter.

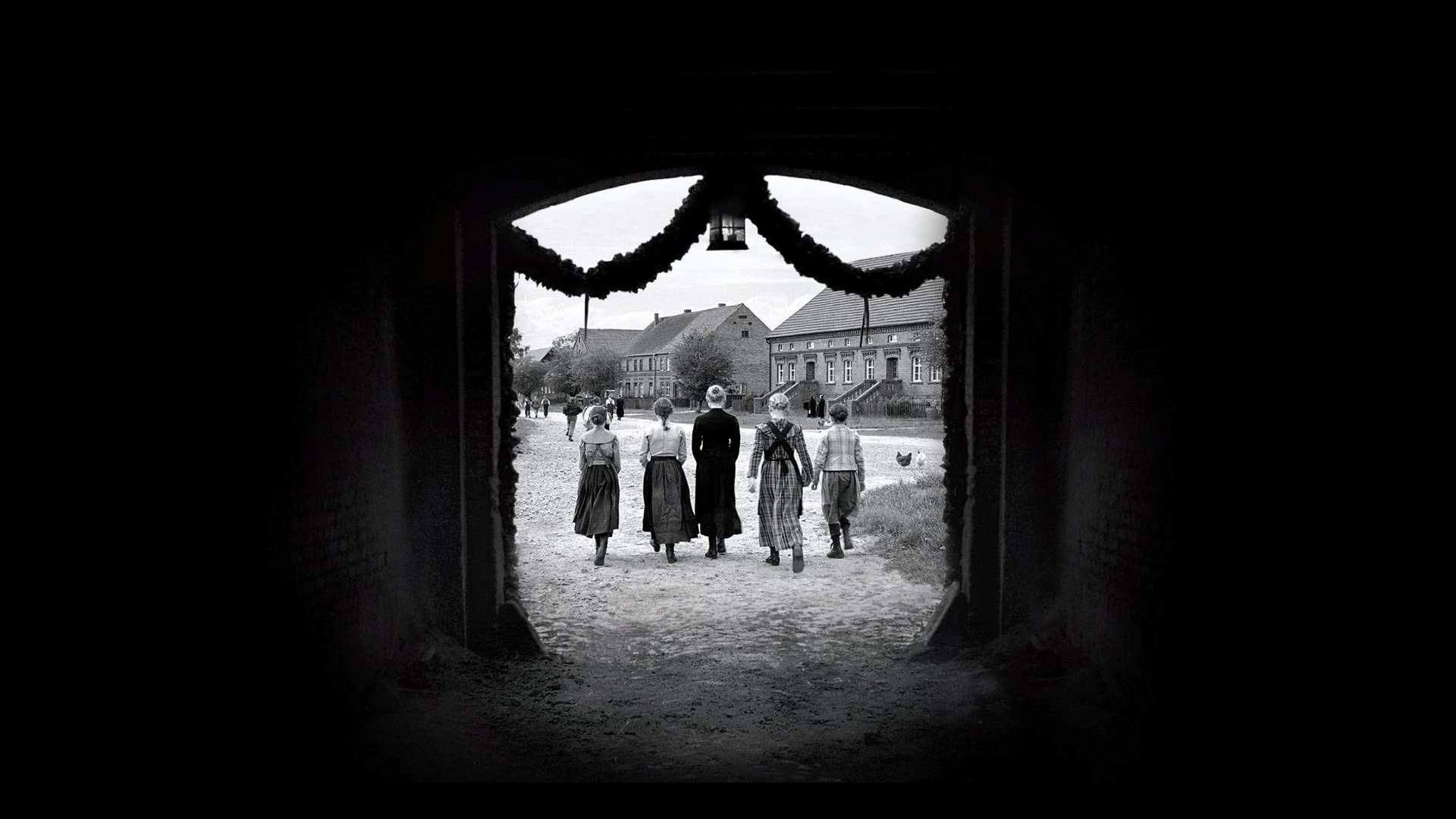

The action unfolds in an intimate setting — within the four walls of a pastor’s house. The plot is simple: the famous pianist Charlotte comes to visit her daughter Eva, whom she hasn’t seen in seven years. Eva lives in isolation with her husband and secretly cares for her younger sister Helena, who is crippled by an incurable illness. Before this, Charlotte had kept Helena in a clinic for years and rarely visited.

The film is divided into two parts: day and night. Daytime — a time of masks, social roles, and ambiguous phrases. Eva says she wishes her mother happiness — and immediately, with malice, talks about her behind her back. Charlotte suffers from loneliness, but in the presence of others, she plays the role of a confident, accomplished woman. Even the inner monologues contradict themselves: the mother seems ready to give her daughter a car, but then we see her choosing a new car for herself. It is a complex game of hints, pauses, and shifted accents, where every statement carries the weight of their past confrontations, and every gesture is both an attempt to reveal and to conceal.

Two Monologues in One Space

The central night scene of the film — an extended, almost unbearably intense episode — becomes a trap for the viewer’s perception. At first, it seems like an exchange of lines, an attempt to put years of pain into words. But Bergman meticulously shows how this appearance is constructed: what we are witnessing are two parallel monologues, sounding side by side but never truly touching. The scene is assembled with extreme precision: close-ups that turn the faces into masks of suffering; a deliberately motionless camera that traps the characters in their positions; editing that emphasizes not connection, but the gap between the lines.

Eva uses speech as a tool of accusation. Her communicative strategy follows the model of a prosecutor’s address. Every word is evidence, carefully gathered and dated. She doesn’t speak so that her mother might finally see her pain as an undeniable reality, but so that her mother acknowledges her guilt as a fact. Her speech is packed with details: hours of waiting by the door while her mother “works”; awkward attempts to “fix” her body and face; the suitcases on the stairs on the day her mother leaves. None of this serves to restore or make sense of the past: it is the evidentiary basis for an already decided verdict.

Charlotte sees her daughter’s words as a threat that must be neutralized. So in her speech, she builds barricades, a system of self-justifications where every argument of her daughter must be recoded. “I did what I could” — a position that turns concrete harm into subjective suffering. Shifting the focus onto herself — complaints about parental neglect, lost contracts, her own timidity — is a classic narcissist maneuver, for whom another’s suffering can only be legitimized through its reflection. The final, “I wanted you to understand that I’m weak too” reinforces a narrative in which the mother’s suffering demands consolation, displacing any other concern.

In this night scene, the last move remains with Eva, and she denies her mother sympathy. Two incapacities collide: the daughter can no longer forgive — just as the mother once could not give her love.

Listening to Not Hear

The act of perception can be no less aggressive than the act of speaking. In Autumn Sonata, listening is an operation of filtering, distorting, and using another’s words. The characters hear only what confirms their preexisting worldview, cutting off anything that might challenge it.

Eva listens to her mother through the lens of years of resentment, aiming to shatter the familiar facade and expose the truth. Any attempt by Charlotte to explain herself is perceived as manipulation; expressions of feeling — as a carefully rehearsed performance. It is no coincidence that Eva takes Helena in: to present her at the right moment as evidence of her mother’s failures and her own superiority. Eva is not seeking a new, unexplored truth in her mother’s words; she needs confirmation of an already formed narrative, where the mother is a monster and a fraud, and the daughter a victim. She is not ready to encounter a living, unpredictable Other who does not fit her own system of coordinates.

Charlotte listens to her daughter differently, but no less aggressively: she searches for weakness, establishes hierarchy, asserts authority. The key scene with Chopin’s Prelude models their relationship: Charlotte listens to Eva’s playing not to connect with her daughter’s inner world or recognize her attempt to speak in the one language that, she had hoped, might unite them. Instead, the mother listens as a supreme authority, spotting technical flaws, misarticulation, and insufficient interpretive depth. Her listening is a display of superiority, disguised as professional critique. When she sits at the piano and plays the same prelude, showing “how it should be done,” she finally denies her daughter the right to her own voice.

Bergman’s choice of the piano as Charlotte’s instrument is a precise metaphor for her way of existing in the world. The piano is an instrument that needs no other. It can fill the entire sound space without requiring an ensemble, without needing a partner. It only speaks — monologically and self-sufficiently.

Looking into the Abyss and Withdrawing

Here we approach the most paradoxical aspect of the film, connected to Bergman’s original intention, which, by his own admission, “failed.” The director wanted to create a story where “the daughter gives birth to the mother” — where Eva, through a brutal yet sincere confrontation, would force Charlotte to be reborn, to become genuine, capable of love. It would have been a story of therapeutic catharsis, where truth leads to healing. But the characters began to live their own lives. Still, at night something occurs that can be called a glimpse of genuine understanding — not complete, not salvational, but real. For a moment, their inner perceptions of each other crack, and through the fissures, the light of another’s truth shines through.

Eva voices her accumulated pain — articulates the structure of her suffering. And suddenly she perceives in her mother a frightened, vulnerable child. She sees that her mother’s selfishness is not evil will, but the result of a fundamental incapacity, almost a deficiency. Charlotte, in turn, looks at herself through her daughter’s eyes and sees the scale of destruction caused by her principle of “music above all.” She realizes that the art she so prided herself on cost her daughter a life: she is unhappy and unfulfilled. Yet this mutual glimpse does not lead to transformation. By morning, both return to their roles. Why?

Bergman shows the tragedy of unchanging characters: Charlotte is too rigid, her narcissism too deeply embedded in the structure of her personality. Her remorse is situational; it acts as a valve to release unbearable pressure. She mourns not her daughter’s crippled life, but her own inadequacy. Her tears are sincere, yet turned inward. Eva, having finally gained the chance to speak, does not use her newfound voice to create something new. She uses it to cement her identity as a victim. Her rebellion was a temporary outburst, and her dependence too enduring. She remains a girl, desperately seeking her mother’s love and fearing rejection.

The gap between understanding and the impossibility of living differently — this is what sustains the dramatic tension of Autumn Sonata.

Helena: Truth and Address to God

In the structure of the film, Helena occupies a special place — she is a living refutation of the entire culture of verbalization, a silent witness to the failure of language. With her entire being, she proves that there is pain that cannot be expressed in words. While Eva and Charlotte weave verbal lace from lies, half-truths, and manipulations, Helena responds to their emotional violence directly. Her seizure during the night conversation, the agonizing slide from the bed, the inarticulate sounds — these constitute the most honest communication in the film. In this cry resonates an ethical imperative: “hear me,” an absolute expression of human vulnerability and the need for the Other.

In Bergman’s world, family, religion, and art are three faces of the same problem: the human connection to the Higher, to the Other, endowed with the power to grant meaning but refusing to answer. Eva and Charlotte’s conversation can be read in this light as a “secular prayer” — a confession addressed to an authority with absolute power over your existence. Eva speaks from the position of one demanding love as the only proof of her worth. Charlotte responds from the position of a deity, protecting her autonomy, freedom, and accomplishments. She hears the complaint but remains herself — cold, occupied, unchanging. The asymmetry of the god–human relationship (as in the parent–child relationship) cannot be overcome.

There is another figure in the film, almost unnoticed against the backdrop of this intense drama between the two women — Eva’s husband, a pastor, who patiently observes what is happening. He listens without intervening. He loves Eva, even when she doesn’t notice him, absorbed in her anger toward her mother. And he gives her freedom, even the kind that leads to suffering. His presence can be read as a hint toward another model of relation to God, silently accompanying. But Eva does not see her husband: she looks only where love has been denied. And so, in the end, her speech inevitably takes the form of an address — to a place from which no reply comes.

A Letter into the Void

Autumn Sonata leaves us with a conclusion that is both frightening and liberating: perhaps the limit of human communication is not to find a common language and achieve clear mutual understanding, but merely to look into the abyss between two minds and acknowledge that no bridge can span it. That we are condemned to subjective isolation, to perpetual misunderstanding, masked by the illusion of verbal exchange. The letter Eva writes immediately after her mother’s departure is not a step toward a new, more mature dialogue, but a symptom of a chronic condition, a desperate attempt to restart the same painful cycle. She reaches out to her mother again, hoping and waiting for a response. The film ends not with reconciliation, but with the recognition of hopelessness — and in this recognition lies its own tragic wisdom, refusing to console the viewer with false hope.